Crafting for Mind and Mood

Woodworking isn’t just about making furniture or art – it’s increasingly recognized as a mindful, healing, and restorative activity. From clinical research to personal anecdotes, evidence suggests that working with wood can reduce stress, improve mood, and even help people heal from trauma. Psychologists note that hands-on crafts like woodworking can induce a “flow” state, provide a sense of accomplishment, and reconnect us with natural materials, all of which contribute to mental well-being landcwoodcarvers.co.ukwilvaco.com. Community programs and therapists are harnessing woodworking as a form of creative therapy for PTSD, anxiety, and addiction recovery. Even historically and across cultures – from Shaker communities to Japanese temple carpenters – woodworking has been viewed as a spiritual or wellness practice. Below, we delve into the emotional and psychological benefits of woodworking, backed by research and real-world examples, for a comprehensive look at “wood and wellness.”

Entering the Flow: Focus and Fulfillment Through Craft

One of the most therapeutic aspects of woodworking is how it draws people into a flow state – a form of deep, focused engagement famously described by psychologist Mihály Csíkszentmihályi. In flow, we lose track of time and become fully absorbed in the task, which brings intrinsic enjoyment and relief from outside worries. Studies confirm that craft activities (from carving to carpentry) readily induce flow by balancing challenge and skill, giving immediate feedback (e.g. seeing a shape emerge from wood), and requiring full concentration frontiersin.org. This deep focus allows a temporary escape from stressors and promotes a sense of accomplishment as a project takes shape frontiersin.org. In fact, research on university students engaging in crafts found that achieving a flow state during creative work led to “positive emotions” and helped them “maintain psychological balance when facing… life pressures” frontiersin.org.

Flow isn’t just pleasant in the moment – it has measurable mental health benefits. As one 2025 study noted, “the flow state enhances self-efficacy… reducing anxiety and depressive emotions” while also bolstering psychological resilience frontiersin.org. The intense focus of flow operates much like mindfulness meditation, keeping the person anchored in the present task instead of ruminating on past or future concerns frontiersin.org. Woodworkers often describe being “in the zone” when planing a board or carving details – hours can pass without notice, and afterward they feel calmer and more centered. Even novice woodworkers report that the concentration required (“you’ve got to concentrate on what you’re doing”) makes them relax and momentarily tune out their troubles reasonstobecheerful.world. In short, woodworking provides a natural pathway into flow, which in turn yields relaxation, enjoyment, and confidence – a potent antidote to anxiety and low mood.

Woodworking as Therapy for Trauma and Stress

Beyond personal hobby, woodworking is increasingly used in therapeutic settings to help people recover from trauma, PTSD, and chronic stress. While formal research on “woodworking therapy” is still emerging, many practitioners view it under the umbrella of art therapy or occupational therapy – and the anecdotal successes are compelling. For example, the U.S. Veterans Administration recently launched woodworking and woodturning workshops as a form of recreation therapy for veterans with PTSD and anxiety. The goal is to provide “an engaging activity for… Veterans who are suffering from anxiety and/or Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder,” giving them focus and hands-on accomplishment in a supportive setting va.gov. Veterans in these programs get guidance in turning wood on a lathe to make objects like pens or bowls, and they leave each session with a finished project – along with boosted confidence. One Marine Corps veteran smiled as he finished a wooden pen and said, “yeah, I enjoy it, it’s a great experience”, noting that he hadn’t worked with wood since high school va.gov. The structured yet creative nature of woodworking provides a safe space for veterans to relax, open up “shoulder to shoulder” with instructors or peers, and rebuild a sense of purpose outside of their pain.

Survivors of trauma have also discovered woodworking on their own as a healing outlet. In interviews, individuals coping with severe PTSD or complex PTSD (CPTSD) describe how carpentry and carving help them process emotions and regain self-worth. For instance, one survivor of childhood abuse shared that as he repaired and built furniture, “I felt the childhood trauma… was communicating with me… it was passion and creativity starting to work from within. I felt alive, validated… woodworking was a painstaking therapeutic challenge”, and it helped him control anger and confusion differentbrains.org. Another trauma survivor noted, “My self-confidence has improved and I’m inspired to live more in the moment and enjoy the process… people struggling with self-esteem who may not see their own value would benefit from woodworking. By learning to create and build… the process and outcome will prove they can make, and are themselves, something to be valued.” differentbrains.org. These personal accounts highlight how crafting tangible objects can restore a sense of competence and identity that trauma often erodes. The act of turning raw wood into something useful or beautiful becomes proof of one’s capability and worth.

Therapists observe that woodworking engages multiple therapeutic factors at once. It provides a mindful distraction from intrusive memories (immersing attention in measuring, cutting, sanding), gives a healthy outlet for aggression or hypervigilance (physical effort in a controlled task), and yields a concrete reward at the end (a finished item to keep or give). In clinical terms, it’s an “artistic endeavor that helps you connect with nature… woodworking has a therapeutic purpose since creating art is a cathartic experience” mentalhealthnewsradionetwork.com. Moreover, the repetitive motions and sensory focus (the sound of saws, the smell of wood shavings) can have a meditative effect, calming the nervous system. As one mental health commentator put it, “Woodworking is a sort of meditation… it requires focus and constant presence… like meditation, it allows us to sail into a whole new world and distance from our problems,” effectively defining woodworking as a mindfulness activity mentalhealthnewsradionetwork.com.

It’s no surprise, then, that some trauma recovery programs have formalized woodworking groups. In Canada, an indigenous carver-therapist worked with residential school survivors, carving together as a way to “process their grief and trauma of past experiences. It creates a space where people can talk… when you’re actually engaged in an activity it loosens up the tongue.” landcwoodcarvers.co.uk This mirrors the approach of Men’s Sheds and veterans’ workshops (discussed below) – use the craft to create a comfortable, non-threatening environment where healing conversations and camaraderie can naturally unfold. In summary, whether in a hospital setting or a community shed, woodworking has shown promise as a complementary therapy to talk counseling, giving people a calming ritual, a creative outlet, and a rebuilding of inner strength.

“Woodshops” for Wellness: Community Programs and Rehab

Woodworking’s therapeutic power has given rise to numerous programs, workshops, and community initiatives that explicitly use craft for wellness. Around the world, these efforts are helping veterans, older adults, and people in recovery find support and purpose. A few notable examples include:

-

Veterans Woodcraft (UK) – Founded by a British army veteran, this project began with impromptu spoon-carving sessions for wounded soldiers and grew into a full nonprofit workshop for ex-service members. Veterans Woodcraft offers woodworking training courses and even a drop-in café and quiet support areas, all “drawing… veterans with mental health issues, drawn… to the therapeutic nature of woodworking.” The founder, who credits his own shed with saving his life during a PTSD crisis, says “for those couple of hours, you kind of relax… that two hours in the workshop can make a huge difference to their wellbeing.” reasonstobecheerful.world What started as one man “pottering around with bits of wood” to cope with grief has become a lifeline for many others – a real testament to woodcraft as group therapy.

-

Men’s Sheds (Global) – The Men’s Shed movement, which began in Australia and spread to the UK, North America and beyond, creates community woodshops where men (and women, in some cases) can socialize, tinker on projects, and support each other. The core idea is to fight social isolation and depression by providing a friendly workshop instead of forcing formal support groups. As one organizer put it, “If you put 12 men in a room and ask them to talk about their feelings, six will leave… But if you put a broken lawnmower in the room and ask them to fix it… those 12 men will know each other intimately [after] a couple of hours” reasonstobecheerful.world. Woodworking and repair projects give members a shared task (“shoulder to shoulder”) that naturally leads to conversation and friendship. Many Men’s Sheds report improved well-being among members; remarkably, a survey of 178 UK sheds found 25% had definitively saved a member’s life (preventing suicide) and another 14% believed they had reasonstobecheerful.world. By pairing hands-on craft with peer support, Men’s Sheds provide purpose, camaraderie, and an antidote to loneliness for retirees, widowers, veterans, and others who join.

-

Woodworking for Veterans (US) – Several American nonprofits and schools have launched programs to teach woodworking to veterans as a form of rehabilitation. For example, Woodworking With Warriors is a U.S. organization whose mission is “to provide alternative therapy activities through traditional hand tool woodworking for veterans and active military personnel.” Similarly, the Purple Heart Project, started by a master craftsman, offers intensive woodworking classes free of charge to wounded veterans, aiming to impart both skills and emotional healing (the motto: “Finding peace and joy through the craftsmanship of hand tool woodworking”). These programs often observe that veterans struggling with PTSD or physical injuries rediscover focus, confidence, and joy by learning to create with their hands. The group therapy element – working alongside fellow vets who “get it” – also leverages shared military experience to build trust and mutual support phirstandlassing.com.

-

Addiction Recovery Workshops – Rehab centers are integrating woodworking into substance abuse treatment, recognizing that creative focus can fill the void that drugs once occupied. A poignant case is Derek Skapars, a recovering alcoholic who found sobriety in woodworking and went on to become a “woodworking therapist” at treatment centers. He explains that staying sober requires being “meaningfully occupied” and that making things with wood gave him fulfillment and new goals to keep addiction at bay capecodtimes.com. Skapars says woodworking helped orient him toward positive habits and service to others – “The first thing I see when I wake up… is my beautiful woodworking. And that’s helped me get through tough moments.” capecodtimes.com His approach as a counselor is hands-on immersion: teaching clients to build Windsor chairs or desks, which engages them fully in the present task. The founder of one recovery program concurs that “being present is a habit” and that “addiction thrives in distraction… [but] gets reset by creating new habit loops”, such as the sustained focus of a craft capecodtimes.comcapecodtimes.com. In practice, many sober living communities now have woodshops or maker spaces where residents craft items (some facilities even have residents build furniture or structures for the program itself). By learning tangible skills and channeling creative energy, people in recovery gain self-esteem, patience, and a constructive hobby to support their sobriety.

These examples demonstrate the versatility of woodworking as a wellness tool – it can be adapted for different groups but tends to produce similar benefits. Participants often report reduced stress and anxiety, improved social connections, renewed purpose, and the simple happiness of seeing their work come to fruition. As one veteran put it, “Once you start feeling better [through woodworking], it’s like dropping a pebble in water… the ripples come back out, and you slowly get back into the community.” reasonstobecheerful.world The ripple effect of these programs extends beyond individual crafters, fostering supportive micro-communities and even benefiting others (through donated projects, mentorship of newcomers, etc.). In a society grappling with mental health challenges, such grassroots woodworking initiatives offer a practical, low-tech therapeutic outlet – no fancy equipment needed beyond wood, tools, and willing hands.

Nature’s Touch: Biophilia and the Calming Power of Wood

Part of woodworking’s restorative magic lies in the material itself: wood, a natural element. Humans have an innate affinity for natural materials and environments – a concept known as biophilia. Working with wood quite literally brings nature to our fingertips, engaging our senses with the sight, touch, and smell of a raw organic substance. Research shows that incorporating wood and other natural elements into our surroundings can have powerful calming and mood-boosting effects. In fact, psychologists have found that simply being around wood (in interior design) can lower blood pressure, heart rate, and stress levels, much like spending time in nature wilvaco.comwilvaco.com. One review of studies noted that environments with visible wood produce “a drop in blood pressure, lower pulse, and a calming effect,” leading to “reduced stress and improved focus.” wilvaco.com This is often called the “biophilia effect,” the idea that bringing bits of nature (wood, plants, sunlight) into daily life nurtures our mental health wilvaco.com.

Wood has unique sensory qualities that contribute to grounding and relaxation. Its warm colors and grain patterns are easy on the eyes, and its tactile feel is comforting – think of the smoothness of sanded timber or the grain under one’s fingertips. “The tactile experience of working with wood and the sensory input from natural textures and scents can have a grounding effect,” notes one carving enthusiast, adding that this “connection to nature has been shown to reduce stress and promote well-being.” thespooncrank.com Unlike plastic or metal, wood “breathes” and often carries a subtle pleasant aroma (like pine or cedar). These sensory cues subtly remind our brains of forests and the outdoors. Occupational therapists sometimes speak of woodworking as a sensory grounding activity: if someone is anxious or dissociating, the feel and smell of wood, the sound of carving, can help anchor them back in the present moment. In PTSD therapy, for instance, focusing on five senses is a known grounding technique – woodworking inherently engages at least three (sight, touch, sound, and even smell), making it an organic way to stay present and mindful.

Biophilic design research further supports that wood environments improve mood and cognitive function. In classrooms, students taught in rooms with wood floors and panels have shown lower stress and even performed better on tests than those in standard classrooms wilvaco.com. In one study, high schoolers in wood-filled classrooms had significantly lower heart rates and reported feeling more at ease than peers in rooms with no wood wilvaco.com. Another experiment in Japan found that touching or even just viewing wood (versus metal) elicited positive emotional responses: “wood had both physiological and psychological advantages… associated with decreased blood pressure and decreased depression or dejection, while steel increased both.” wilvaco.com In short, wood as a material appears to have a soothing, uplifting influence on the human nervous system – perhaps because it connects us to the natural world from which we evolved.

When we engage in woodworking, we amplify this connection. We’re not only around wood; we are actively shaping it and often doing so in a natural setting (a shed, a garage with the door open, or outdoors). Many woodworkers prefer using reclaimed or “green” wood (freshly cut branches, logs, etc.), which further deepens the feeling of working with nature rather than against it. In wood carving circles, people often speak of “listening to the wood” or respecting its grain and imperfections – an almost collaborative dance with the material. This mindset can be profoundly calming. A woodcarving study noted that “woodcarving fosters a connection to nature. Especially when carving green wood, the carver becomes part of where the wood comes from.” landcwoodcarvers.co.uk Such a process can evoke feelings of groundedness and belonging in the natural cycle, countering the alienation many feel in hectic modern life.

All of this aligns with eco-psychology theories that nature engagement relieves stress and improves mental health apa.orgmentalhealth.org.uk. Woodworking, by virtue of its medium, is a hands-on way to get those benefits without needing a forest trek. A therapist writing about woodcraft put it beautifully: “Using our hands and making things… It is in our nature to create… arts [and crafts] became popular since the 50s as therapeutic tools… woodworking and woodcarving [help in] the healing process.” mentalhealthnewsradionetwork.com The biophilic comfort of wood may be one reason crafts like woodworking, pottery, gardening, etc., are broadly healing: they reintroduce natural patterns and sensations into our daily experience. In practical terms, spending a few hours in a woodshop, smelling sawdust and handling lumber, can be as restorative for some people as a walk in the woods – it’s a form of “bringing nature inside” and engaging with it creatively.

Sustainability and Purpose: The Joy of Reclaimed Wood

Working with wood also offers an added dimension of purpose when it intersects with sustainability. Many woodworkers take pride in using reclaimed wood – salvaged lumber from old barns, discarded furniture, fallen trees, and so on – to create something new. This practice not only benefits the environment by reducing waste and demand for fresh timber, but it can deeply enrich the meaning of the craft for the individual. There’s a special satisfaction in giving new life to wood that has its own history; the process becomes symbolic of renewal and resilience, which can mirror a person’s own healing journey.

Architects and designers have noted that reclaimed wood in spaces “delivers emotional connection and a greater biophilic effect” than newly milled wood terramai.comterramai.com. The patina, weathering, and even nail holes in reclaimed boards tell a story, which people intuitively respond to. As one design article explains, “The wood’s history enhances the occupant’s experience in an authentic and meaningful manner… We all love a good story, especially when the story taps into our emotions. Occupants will connect with reclaimed wood.” terramai.com In the context of personal woodworking, using reclaimed materials can give the maker a sense of participating in that story. For example, a veteran with PTSD named Rolando Corral found purpose by crafting wooden American flags out of reclaimed wood – he founded a small business that not only sells these flags but also donates them to charities and fellow veterans differentbrains.org. His inspiration literally came in a dream of being in nature and building a flag from old wood to save a comrade: “In the dream… a veteran and I built a wooden American flag out of reclaimed wood and I convinced him not to commit suicide.” differentbrains.org This vision led him to create I.G.Y. Wood Creations, with a mission to “restore hope for military veterans and first responders through reclaimed wood.” differentbrains.org For Corral and many like him, sustainability and service blend with craftsmanship – each piece of reclaimed wood becomes a testament to survival and hope, both for the material and the maker.

On a more everyday level, hobbyist woodworkers often talk about the mindfulness of using every bit of wood and respecting the resource. Salvaging wood can instill a sense of values and mindfulness: you slow down, plan cuts carefully to avoid waste, and appreciate the uniqueness of each weathered plank. This attitude transforms woodworking from just a weekend hobby into a small act of environmental stewardship. Knowing that one’s craft is eco-friendly can enhance self-esteem and purpose – you’re not only creating for yourself, but also contributing to sustainability. Psychological research on meaning and well-being finds that engaging in activities aligned with one’s values (such as environmentalism) boosts life satisfaction and reduces stress blog.zerocircle.eco publichealth.jhu.edu. Thus, a woodworker who cherishes reclaimed wood might feel a deeper sense of fulfillment than if they bought all new lumber. Every time they pick up a piece of old wood, they are reminded of resourcefulness, history, and the good feeling of not letting things go to waste.

Furthermore, reclaimed wood often comes from interesting sources – maybe an old ship, a historic building, or a fallen urban tree – which can spark gratitude and reflection. Some describe it almost spiritually: the wood “wanted” to be something again. In Japanese woodworking (as we’ll see next), using wood that has died of natural causes or recycling wood is part of showing respect to nature’s materials japanwoodcraftassociation.com. In a similar spirit, Western craft traditions like the Arts and Crafts movement held that honest, sustainable use of materials was integral to “good craft” and moral well-being. Modern sustainable woodworking carries on that idea: the process of thoughtfully reclaiming and crafting wood can make the woodworker feel more connected to the earth and community, reducing the sense of isolation or aimlessness that fuels much modern stress. In summary, sustainability in woodworking isn’t just good for the planet – it can also be deeply therapeutic for the soul, giving the craft a higher purpose and imbuing each creation with an extra layer of meaning.

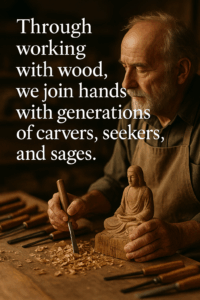

Crafting as a Spiritual Practice: Traditions and Philosophy

The notion that working with one’s hands in wood can be spiritual or life-enriching is not new. Across history, various cultures and traditions have viewed woodworking and craftsmanship as a path to something higher – whether that be communion with God, harmony with nature, or personal enlightenment. These philosophies resonate with the idea of woodworking as more than a hobby; it can be a form of meditation, devotion, or philosophy in action.

In the Shaker tradition of 18th-19th century America, for example, craftsmanship was literally intertwined with religious practice. The Shakers, a utopian Christian sect, believed in “hands to work, hearts to God.” Everyday labor and fine craft were seen as a way to experience the sacred. As one account of Shaker life notes, “The Shakers believed that the sacred could be experienced through mindful labor, whether that was highly skilled craftwork or domestic chores.” ecotonemagazine.org In Shaker communities, making well-crafted furniture, tools, and buildings was a form of prayer – the attention to simplicity, quality, and honesty in woodworking was a reflection of their spiritual ideals. Shaker furniture’s elegant simplicity isn’t just aesthetic; it stemmed from a belief that making something well (and with love and focus) was in itself a holy act. This historical perspective adds weight to modern observations that woodworking feels meditative – the Shakers would agree that mindful craft can uplift the spirit.

In Japanese culture, woodworking carries a deep spiritual significance through Shintō and Zen beliefs. Shintō, the indigenous faith of Japan, teaches that spirits (kami) reside in natural objects, including trees and wood. Traditional Japanese carpenters embrace this “animistic belief in the ‘spirit of wood’,” which encourages them to work with the wood’s nature rather than forcefully against it japanwoodcraftassociation.com. Master carpenters building temples or tea houses historically performed rituals and approached their work with reverence, believing the wood and the tools carried spiritual energy. As the Japan Woodcraft Association describes, “In Japan, nature, religion and craft are deeply intertwined… Shintō places a spiritual essence in all things: animals, plants, rocks and of course, wood. This pushes Japanese woodworkers to work with, rather than against, nature.” japanwoodcraftassociation.com In practice, this might mean honoring the natural grain and curves of a timber, or using wood that has naturally fallen. The famous temple carpenters (miyadaiku) of Japan wear traditional attire and sometimes even purify materials before construction, signifying the sanctity of their craft. The philosophy of wabi-sabi (finding beauty in imperfection and impermanence) also influences Japanese woodworking – every knot or weathered feature in wood is appreciated, not rejected. This ethos can make the act of woodworking profoundly contemplative and respectful, fostering patience and a sense of unity with nature. Western woodworkers often admire Japanese joinery not just for its technical brilliance, but for the Zen-like discipline and spiritual calm it embodies.

In Vedic and Hindu traditions of India, carpentry (known as Takshana) has long been esteemed as a noble, almost sacred craft. Ancient Vedic texts mention the carpenter (Sutradhara or Takshaka) in the same breath as priests and scholars, responsible for building altars, chariots and temples according to divine proportions theintactone.com hindusanatanvahini.com. The work of carving and constructing was seen as “linking human dwellings… with cosmic order,” guided by scripture (Shilpa Shastras) that integrated spirituality with design theintactone.com. Notably, traditional artisans in India often approached long projects “as a form of spiritual practice.” Historical accounts of the Sutar caste (woodworkers) say that “Projects that spanned months, sometimes even years, were approached as a form of spiritual practice… The delicate carvings on temple ceilings were not merely decorative – they expressed deep spiritual sentiments.” hindusanatanvahini.com Indeed, carving a temple or even a household shrine was an act of devotion. The Hindu concept of Vishwakarma, the divine architect/carpenter of the gods, further underscores that making things by hand can be close to godliness. Even today, many Indian carpenters will start new projects on Vishwakarma Puja (a festival honoring craftsmen), essentially blessing their tools and work. This tradition highlights the pride and sacredness associated with woodworking – creating with wood is creating in harmony with the universe’s design, a perspective that can imbue the craftsman with purpose and reverence.

These historical and cultural viewpoints echo a common theme: craft feeds the soul. Whether it’s a Shaker elder smoothing a chair rung in prayer, a Japanese artisan listening to what the wood “wants to be,” or an Indian master carving deities into teak with mantra-like patience, woodworking has been a conduit for mental and spiritual well-being. In today’s secular world, a hobbyist might not label their woodworking as spiritual, but many describe similar feelings – a sense of peace, clarity, and connection that is hard to find elsewhere. As one modern carver put it, perhaps only half-jokingly, “human beings are animals that are wired for and meant to create with their hands… there’s a big resurgence of people going back to traditional activities for their soul and their spirit and reconnection.” landcwoodcarvers.co.uklandcwoodcarvers.co.uk In short, when we pick up tools and shape wood, we’re tapping into an age-old human rhythm that nourishes us on a deeper level. The craft itself becomes a teacher of life lessons – patience, humility (mistakes will be made!), attention, and care.

Conclusion: Healing in the Grain of Wood

From neuroscience to nostalgia, the case for woodworking as a healing, mindful practice is strong. It engages our hands, minds, and hearts in unison: hands busy with tools, mind focused on the present task, and heart finding joy in creativity and connection. The simple act of cutting, carving, or sanding wood can unlock the flow state, that productive calm where worries fade and self-esteem grows with each accomplishment frontiersin.org. Therapeutically, woodworking provides a constructive outlet for processing trauma and stress – it’s hard to ruminate on anxiety when you’re measuring dovetail joints or carefully whittling a spoon. For many veterans, survivors, and people in recovery, it has opened a door to talking less and doing more, rebuilding confidence one project at a time. The social dimension – whether in a men’s shed, a VA workshop, or a weekend class – adds the benefit of camaraderie and support that is inherently nonjudgmental (the wood doesn’t care what you’ve been through, and neither do fellow woodworkers absorbed in their own creations).

Crucially, woodworking reconnects us with the physical world and nature’s gifts. In an era when so much of life is virtual and instantaneous, the slow, tactile process of shaping wood is grounding. The scent of cedar, the warm hue of oak, the ring patterns telling a tree’s life story – all these remind us that we too are part of nature, growing and adapting with each season. Research shows that bringing wood and natural elements into our environment “has a similar stress-reducing effect to nature” itself wilvaco.com. Little wonder that woodshops often feel like sanctuaries: they are places where human creativity and nature’s material meet in harmony. Every finished piece, be it a rough birdhouse or a fine cabinet, embodies that harmony and gives the maker a sense of pride and meaning.

Even the ancients understood that well-being can be crafted. The traditions of Shakers, Japanese carpenters, and Vedic artisans teach us that working wood with care and intent can be a path to inner peace, moral virtue, or spiritual fulfillment. Today’s science might call it “behavioral activation” or “flow therapy,” but at heart it’s the same truth: creative manual work heals. In the words of one veteran-turned-woodworker, “It’s not an overnight cure… but those two hours in the workshop can make a huge difference.” reasonstobecheerful.world Small slices of relief add up, and the ripple effects – more confidence, less stress, new friendships, a reclaimed sense of purpose – extend into daily life.

Wood and wellness, craft and cure: it’s a synergy that more people are rediscovering. Whether you’re struggling with trauma, seeking stress relief, or just longing for a fulfilling hobby, the humble act of making things from wood offers a therapeutic journey. Grab a piece of wood, pick up a tool (even if it’s just sandpaper and a block of scrap), and you may find that in caring for that wood – coaxing it into form – you end up caring for yourself in the process. As countless woodworkers have learned, there’s healing in those shavings and hope in the grain of a new creation. In crafting something, we often craft ourselves anew – calmer, stronger, and more connected to the world around us.

Sources: The insights above are supported by a range of sources, including academic studies on crafts and mental health frontiersin.org, interviews with woodworker-therapists and participants differentbrains.org, veterans’ program reports va.gov, biophilic design researchwilvaco.comwilvaco.com, and historical analyses of craft traditions ecotonemagazine.org japanwoodcraftassociation.com. These references, along with others cited throughout the text, provide evidence for the psychological benefits and rich context of woodworking as a mindful, healing practice. Each citation points to the original source material for further reading on this fascinating intersection of craft and well-being.